The flu pandemic of 1918 influenza pandemic took more lives than any other epidemic in human history. This was a time before the nature of viruses was understood, and long before there was any antiviral treatments. But our modern day understanding of why this virus was so virulent compared to the seasonal influenza we experience annually would await the retrieval of frozen material from a century ago, and the reconstruction of the virus and testing, both requiring research with mice and chicken eggs.

Despite this influenza pandemic being called the “Spanish flu,” it was first identified in military personnel at Fort Riley in Kansas in the spring of 1918. World War I was underway and the transport of troops aided its spread worldwide during 1918-1919. According to the CDC website addressing the history of this pandemic, about one-third of the world’s population, about 500 million, were infected. In the United States, about 675,000 people died.

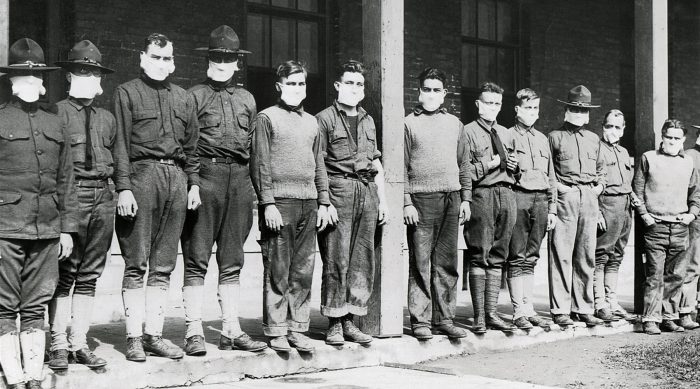

The largest number of deaths occurred in children under 5 years old, adults age 20-40, and the elderly over 65. With no antivirals, vaccines or antibiotics (antibiotics do not affect viruses but could have treated secondary bacterial infections), the medical community was left with the mitigations that we are again using today: social distancing and isolation, quarantine, handwashing and personal hygiene, disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings including schools and courtroom proceedings. Since up to a third of medical doctors were deployed with troops, retired healthcare folks and all levels of nurses were called into duty. With many workers lost to the illness, some businesses were forced to close.

But what makes this pandemic of 1918 so much more deadly than our much milder seasonal flu virus? The research into this is also explained on the CDC website in: “The Deadliest Flu: The Complete Story of the Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus” by Douglas Jordan with contributions from Dr. Terrence Tumpey and Barbara Jester.

In 1951, professor Johan Hultin and his colleagues traveled to the Brevig Mission burial site. 72 of the village’s 80 adults died within five days and were buried and preserved by the permafrost. He received permission to harvest frozen lung tissue from a preserved body. But with the technology of the time, it proved impossible to retrieve the virus.

Modern techniques improved significantly in modern times and Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger and Dr. Ann Reid were able to determine a partial genetic sequence from the 1918 virus from tissue collected and preserved from a soldier who died of flu in 1918 in South Carolina.

Forty-six years since his initial attempt, Hultin returned and again excavated the permafrost of the burial site. The frozen lung tissue he sent back made it possible to sequence the full genome of the 1918 flu virus in 1999. Further analyses found this virulent virus strain “… likely was an ancestor or closely related to the earliest influenza viruses known to infect mammals” and most closely related to the oldest classical swine influenza strain.

It was suspected that there were likely many genetic factors causing the 1918 virus strain’s virulence.

Hultin’s samples again allowed researchers to further research into why. To test the factors for virulence would eventually require reconstructing the live virus. Dr. Peter Palese and his colleagues had perfected a process where plasmids could be used to do this.

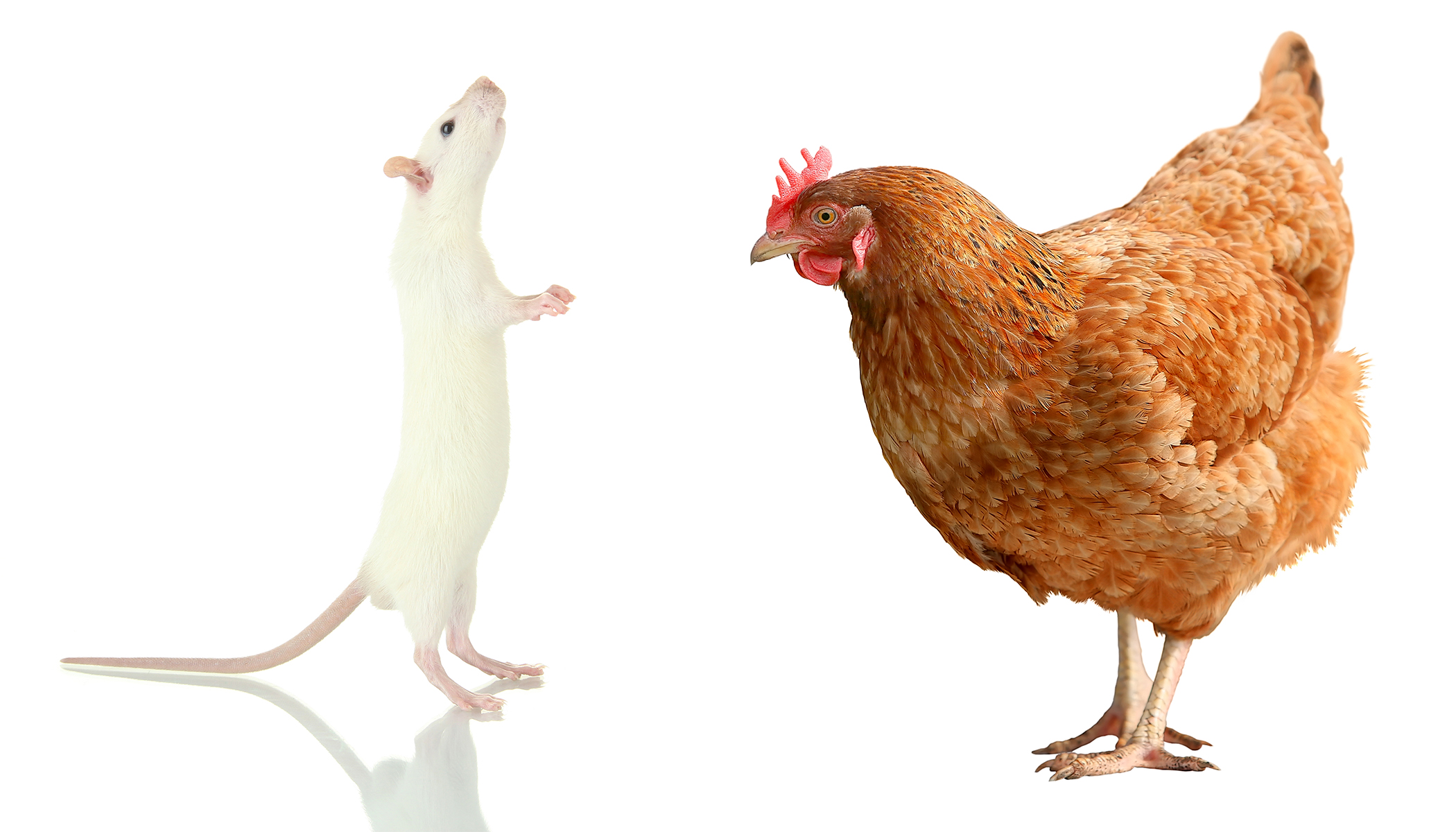

The reconstruction of the influenza virus of 1918 took place in very secure facilities and after passing much review for biosafety, could only be conducted in a special CDC facility by one researcher, with substantial precautions taken to prevent its release: Dr. Terrence Tumpey. Once the virus was reconstructed and multiplied in eggs, it was then available for testing on mice. The extreme virulence was obvious in the lung tissues of infect mice, the same effect seen in victims in 1918.

Additional experiments with 10-day old fertilized chicken eggs led to understanding that “the constellation of all eight genes together make an exceptionally virulent virus.” The common seasonal flu viruses were not anywhere as virulent. The conclusion: “In that way, the 1918 virus was special – a uniquely deadly product of nature, evolution and the intermingling of people and animals. It would serve as a portent of nature’s ability to produce future pandemics of varying public health concern and origin.”

In view of this amazing research, the CDC website concludes: “If a severe pandemic, such as occurred in 1918 happened today, it would still likely overwhelm health care infrastructure, both in the United States and across the world. Hospitals and doctors’ offices would struggle to meet demand from the number of patients requiring care. Such an event would require significant increases in the manufacture, distribution and supply of medications, products and life-saving medical equipment, such as mechanical ventilators. Businesses and schools would struggle to function, and even basic services like trash pickup and waste removal could be impacted.”

For illustrations and details on the Flu of 1918 pandemic, see CDC’s 1918 (H1N1 virus) website.

Tags: ArticleNAIA focuses on improving animal wellbeing and preserving the human-animal bond. To accomplish this goal, it is necessary to provide fact-based explanations of complex, often emotionally charged animal issues, while exposing the hype and misinformation that often surrounds them. If our perception is not shaped by reality, even the best and brightest among us cannot reach sound decisions. We created Consider the Source to assist people as they seek factual information about widely misunderstood and controversial issues.

.

.

Comments are closed here.